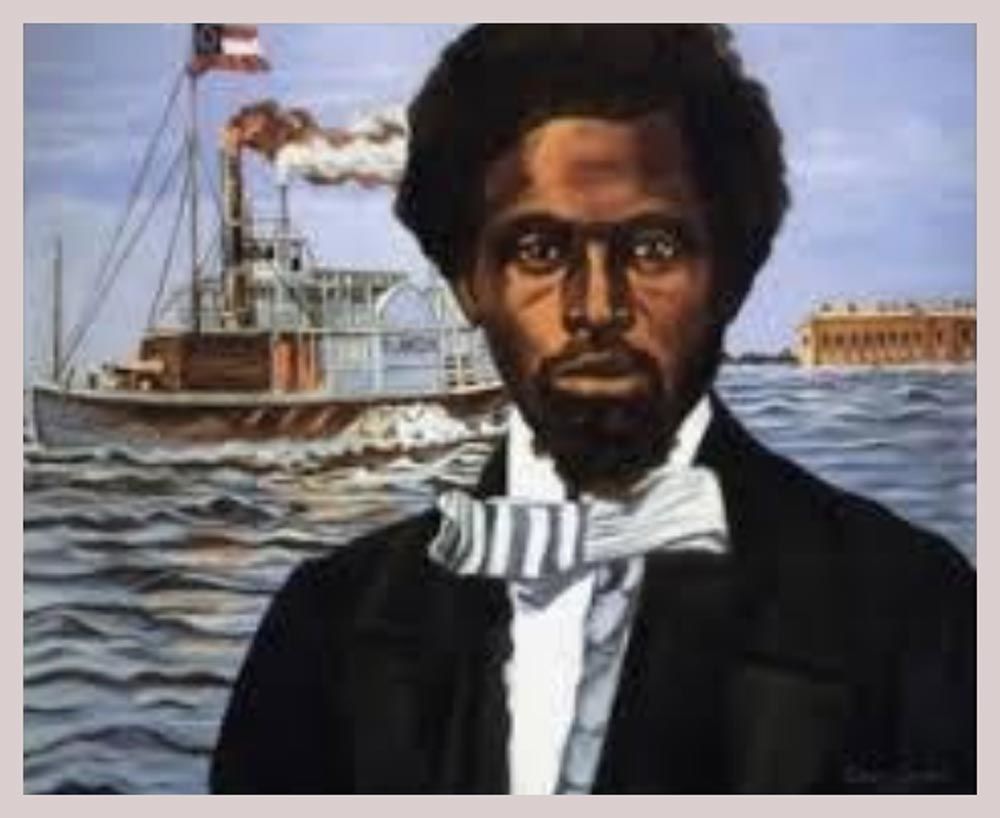

T he large side wheeler backed away from the wharf in the pre-dawn darkness, blew its whistle, and steamed through Charleston harbor flying the Confederate flag. The Planter flashed the correct signals, got clearance from the watch, and steamed straight at the Federal ships blockading the outer harbor. Alarms soon sounded on the Union vessels and the USS Onward came about, lifted big gun number three, and prepared to blast the Confederates speeding toward them. Then someone on deck shouted to hold fire. The Planter had run a dirty white sheet up its mast. Soon everyone could see that its jubilant crew were contraband—fleeing slaves. Their leader, Robert Smalls, had meticulously planned the dash for freedom. He became an instant hero and, as The New York Times reported, met “wild and prolonged cheering” when he and his family, who had been on board, landed in New York.

Smalls joined the Union Navy and rose to the rank of acting captain for his cool head under fire. After the war, he received a bounty for capturing an enemy ship and used it to buy the McKee house in Beaufort, South Carolina—the very house where he had been kept a slave. Smalls went on to represent South Carolina in the US Congress for five terms. In one of his last political acts, he played a futile role at the 1895 South Carolina constitutional convention that rewrote the laws to drive African Americans out of politics.

Smalls’ last frustrated speech at the convention proposed that any white cohabiting with a black should be banned from public office and any child from the union should inherit the father’s name and property. After all, he told the delegates, if a black man improperly approached a white woman, he would be hanged. But any convention that was asked to apply justice to a white man who had debauched a black woman would immediately adjourn for lack of a quorum. The white delegates, temporarily embarrassed, declined to adopt the Smalls amendment and pressed white supremacy into law.

Robert Smalls embodied the vertiginous black experience during the Civil War era. African Americans repeatedly disrupted the white republic. Slaves ran to freedom before the war, subverting the rickety compromises that tried to keep the country together by using harsh fugitive slave laws as a bargaining chip for peace between the North and the South. They burst out of bondage during the war and ran (or, in Smalls’ case, sailed) toward union lines, transforming the military facts on the ground. Some two hundred thousand African Americans served in the Union army and navy—a vital lift in the grinding war of attrition.

The war made a new country. African Americans struggled to build communities, unite families, educate children, enter politics, and get ahead. But the backlash was ferocious. Black Americans faced a trial by fire—long, violent, waves of terror that went on for decades and slowly crushed the civil rights they had won. Smalls went down, at the South Carolina constitutional convention, pointing at the hypocrisy of a society that murdered black men for allegedly crossing the same sexual boundaries which white men insouciantly transgressed.

{Republic of Wrath, pages 128-9}